Engineering Career Development: Lessons from the 2025 Young Woman Engineer Finalists

Awards ceremonies tend to highlight exceptional achievements—the top 1-3% of talent who've navigated their fields successfully. The 2025 Young Woman Engineer finalists represent exactly this: high-performing early-career engineers (typically 3-8 years post-qualification) working across space, aviation, civil engineering, and renewables.

- Technical review: Thomas Jevons (Head of Training, 20+ years)

- Employability review: Joshua Jarvis (Placement Manager)

- Editorial review: Jessica Gilbert (Marketing Editorial Team)

- Last reviewed:

- Changes: Updated for 2025 Young Woman Engineer finalists, current UK engineering workforce data (16.9% women), and professional registration guidance

Awards ceremonies tend to highlight exceptional achievements—the top 1-3% of talent who’ve navigated their fields successfully. The 2025 Young Woman Engineer finalists represent exactly this: high-performing early-career engineers (typically 3-8 years post-qualification) working across space, aviation, civil engineering, and renewables.

But here’s what makes these finalists worth analyzing beyond just celebrating their individual success: The patterns in how they built their careers—early site experience, systematic CPD documentation, strategic networking through professional bodies, hybrid education pathways combining academic and vocational training—are largely replicable for anyone entering engineering.

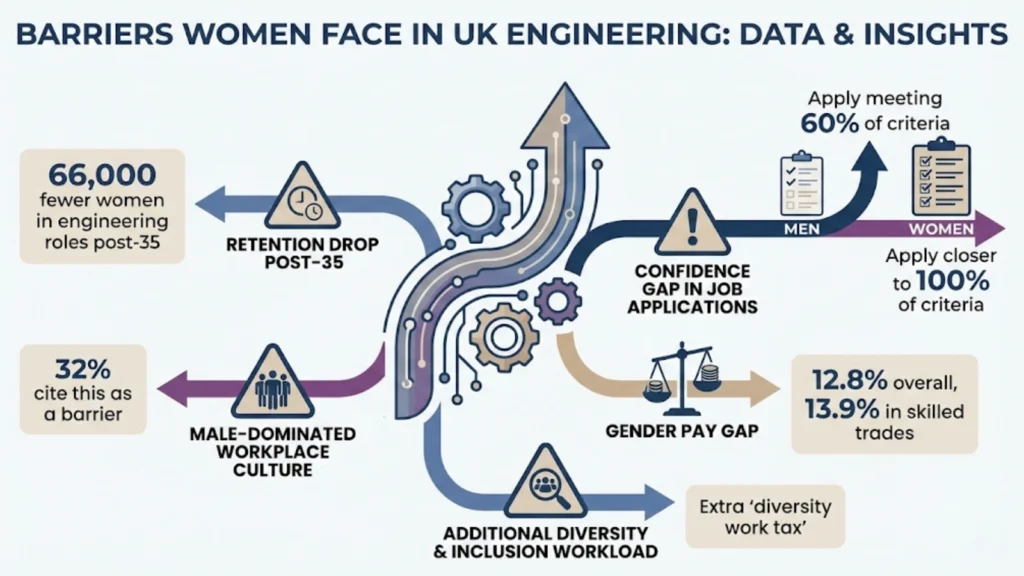

The context these patterns exist within, however, reveals significant challenges. Women comprise only 16.9% of the UK’s 6.4 million engineering workforce, compared to 56% representation in other occupations. Girls’ interest in tech careers sits at 23% versus 52% for boys. Retention drops sharply post-age 35, with 66,000 fewer women in that demographic. The gender pay gap in skilled trades reaches 13.9%, and barriers like male-dominated culture affect 32% of women in engineering according to IET research.

The finalists succeeded despite these structural issues, not because the issues don’t exist. Their progression strategies—seeking mentorship, pursuing professional registration early, documenting competence systematically, building visibility through awards and ambassadorship—worked within a system that remains challenging for most women entering engineering.

This analysis separates what’s genuinely replicable (vocational pathways, apprenticeship outcomes comparable to degrees, mentoring programs improving retention by 20%, competence-based progression through UK-SPEC standards) from what represents selection bias toward already-high-achievers with supportive employers allowing time for outreach and award applications.

The goal isn’t to suggest “just work hard and you’ll win awards.” It’s to identify specific, evidence-based career development behaviors that accelerate progression—for women, for men, for anyone navigating early-career engineering in the UK—while acknowledging the structural barriers that make progression unnecessarily difficult for underrepresented groups.

Who the Finalists Actually Represent

The 2025 Young Woman Engineer finalists occupy a specific position: high-performing early-career talent with 5-10 years post-qualification experience, typically holding roles like senior systems engineer, associate engineer, or technical lead.

Sectors represented:

Space engineering (systems integration, payload design) Aviation (apprenticeships progressing to technical specialist roles) Civil engineering (foundation consultancy, infrastructure projects) Renewable energy (sustainability-focused engineering roles)

These sectors overrepresent high-visibility fields (space tech, renewables) compared to traditional manufacturing or plant engineering where the bulk of UK engineering employment actually exists.

What makes them exceptional (and therefore not entirely representative):

Access to supportive employers: Large organizations (Rolls-Royce, AtkinsRéalis, major consultancies) that provide time and resources for professional development, outreach activities, and award applications. Engineers in small-to-medium enterprises (SMEs) often lack this infrastructure.

Early professional affiliation: Nearly all finalists joined professional bodies (IET, ICE, IMechE) early in their careers, accelerating access to mentoring and networking that isn’t automatically available to all early-career engineers.

Hybrid education pathways: Many combined degrees with apprenticeships, industrial placements, or employer-sponsored training—pathways requiring employers willing to invest in development rather than just filling immediate technical roles.

STEM ambassadorship: 100% of finalists serve as STEM ambassadors. This is an award requirement, so it’s a selected trait rather than necessarily causal for engineering competence. However, the visibility and communication skills developed through ambassadorship do contribute to career progression.

Selection bias toward resilience: Finalists who persisted through male-dominated environments, site-based isolation, or career pivots represent survivorship—not everyone facing these barriers continues in engineering. Understanding what made persistence possible (supportive managers, strong networks, financial stability) matters as much as individual determination.

Regional concentration: London and South East dominate in terms of “visibility” opportunities (awards, conferences, professional body headquarters). Northern England and Midlands offer more “technical depth” opportunities in manufacturing but less professional networking infrastructure.

The limitations in extrapolating from finalists to broader engineering career advice:

You can’t assume typical early-career engineers have access to the same employer support, networking opportunities, or financial stability that allowed finalists to pursue additional qualifications, ambassadorship, or unpaid professional development activities.

The finalists underrepresent regional engineers outside major cities, engineers in traditional manufacturing (vs high-tech sectors), and those from working-class backgrounds where engineering wasn’t a family expectation or early exposure.

What remains valuable: The specific behaviors finalists employed—systematic CPD documentation, early pursuit of professional registration, seeking mentorship, building site experience strategically—are replicable regardless of individual circumstances, even if the pace of progression may differ based on available support systems.

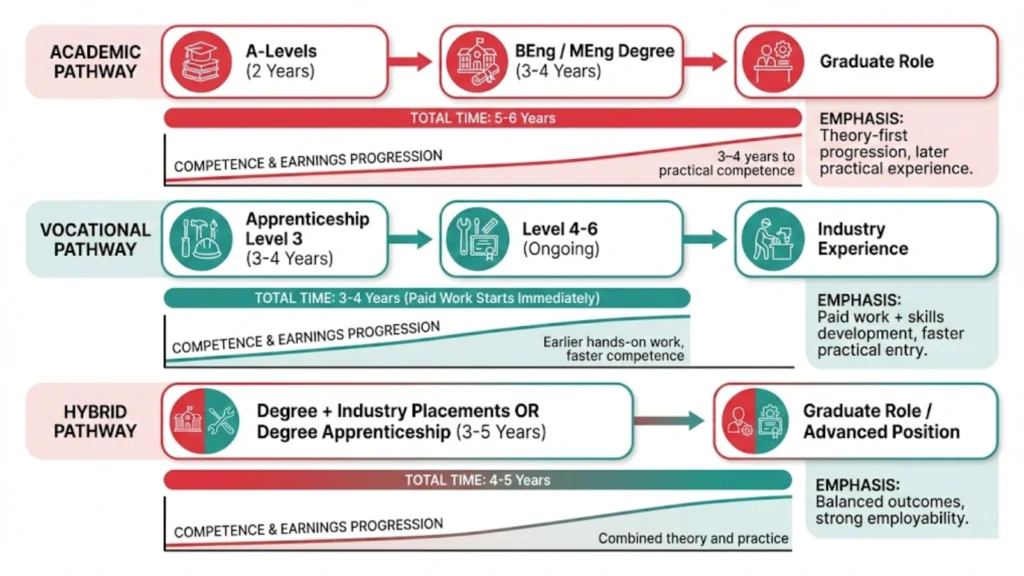

Education Pathways: Vocational, Academic, and Hybrids

The finalists demonstrate that engineering career success increasingly comes from hybrid pathways combining academic knowledge with practical workplace competence, rather than purely university or purely apprenticeship routes.

Degree + placements pattern:

Several finalists completed engineering degrees (BEng/MEng) with substantial industrial placement years embedded. This provides theoretical foundation while building workplace competence, professional networks, and employer relationships that often convert to graduate job offers.

Evidence: EngineeringUK data shows degree apprenticeships (combining both) have higher retention rates than traditional full-time degrees, partly because learners maintain income and employer connection throughout.

Apprenticeship-to-technical-lead trajectory:

Finalists from apprenticeship backgrounds (particularly degree apprenticeships at Level 6/7) reached “Lead” or “Senior” status faster than traditional graduates in some cases, having accumulated 3-4 additional years of industry experience by age 25.

Evidence: DfE statistics show Level 6 apprenticeships (degree level) achieve comparable earnings to traditional graduates while providing continuous employment. Women represent 17% of engineering apprenticeship starts, lower than overall workforce but growing.

Career switcher routes:

Some finalists entered engineering mid-career from unrelated fields, typically through conversion courses, foundation degrees, or employer-sponsored training programs designed for career changers.

Challenge: Self-doubt appears more frequently in career switcher narratives (qualitative X/forum signals), particularly for women questioning whether they’re “too old” or lack sufficient background despite having transferable project management, problem-solving, or technical skills from previous roles.

T-Levels and emerging pathways:

While too new for most finalists, T-Levels (technical qualifications for 16-18 year olds) are beginning to create alternative routes. Currently only 12% of T-Level engineering students are girls, indicating the gender gap persists at entry level despite curriculum modernization.

What vocational routes provide:

Earlier earnings (paid throughout training vs student debt) Workplace competence from day one (employers value demonstrated ability over theoretical knowledge) Employer networks and references (critical for post-qualification job security) Practical problem-solving skills (learning by doing rather than abstract principles)

What academic routes provide:

Deeper theoretical foundation (beneficial for complex system design, R&D roles) Broader subject exposure (universities cover wider range of topics than single employer) Research skills and critical thinking (valuable for innovation-focused roles) Traditionally higher status (though this perception is slowly changing as apprenticeship outcomes improve).

The Wolverhampton training supports skill development through regional vocational infrastructure that demonstrates how local technical education can provide practical competence alongside theoretical learning, particularly for those entering engineering trades.

Hybrid advantage:

Finalists with hybrid backgrounds (degree + apprenticeship, or academic qualification + substantial placements) often demonstrated superior adaptability—comfortable with both theoretical analysis and practical implementation. This aligns with employer surveys (IET) emphasizing “industry-ready” graduates need both knowledge and workplace competence.

The practical implication: If you’re choosing educational pathway, consider whether you can combine both rather than selecting one exclusively. Degree with year-long placement, degree apprenticeship, or apprenticeship followed by part-time degree all provide hybrid benefits.

The Skills That Actually Drive Progression

Analyzing finalists’ career trajectories reveals four skill categories that enable advancement, with employers increasingly prioritizing combinations rather than deep expertise in just one area.

Technical skills (discipline-specific):

Systems thinking: Ability to understand how components interact within larger infrastructure. Finalists in space engineering, for example, demonstrate payload systems integration rather than just single-component design.

Specialist software proficiency: CAD (AutoCAD, SolidWorks), simulation tools, data analysis platforms. However, employer surveys (IET) indicate competence matters more than brand-name qualification—demonstrated ability to produce accurate technical outputs beats certification alone.

Materials knowledge and testing: Understanding material properties, failure modes, testing protocols. Particularly valued in structural, civil, and aerospace roles where safety is critical.

Regulatory compliance: BS/EN standards, sector-specific regulations, health and safety requirements. Engineering work must meet legal standards—finalists demonstrate thorough understanding of applicable frameworks.

Professional skills (transferable across roles):

Stakeholder management: Communicating technical concepts to non-technical decision-makers (clients, finance teams, senior management). ONS data links strong communication skills to lower pay gaps—roles valuing these skills show better gender parity.

Project coordination: Managing timelines, budgets, resources, and multi-disciplinary teams. Finalists often progressed to “lead” roles based on demonstrated coordination ability rather than just technical brilliance.

Commercial awareness: Understanding how engineering decisions impact business outcomes, cost-benefit analysis, value engineering. Employers increasingly expect engineers to think beyond pure technical optimization.

Written communication: Technical reports, proposals, documentation. Poorly written engineering reports create costly misunderstandings—clear technical writing is a career multiplier.

Digital and emerging skills:

Data literacy: Analysis of large datasets, identifying patterns, using data to inform engineering decisions. The shift toward “digital twins” (virtual models of physical assets) and predictive maintenance requires engineers comfortable with data analysis.

IoT and connectivity: Understanding how physical systems integrate with digital monitoring and control. Finalists increasingly work on projects involving sensor networks, remote monitoring, and automated systems.

AI/ML awareness: Not necessarily building AI models, but understanding where machine learning can optimize engineering processes and how to work with data scientists on integrated solutions.

Workplace behaviors (often overlooked but critical):

Initiative and self-direction: Identifying problems without being told, proposing solutions, taking ownership of outcomes. Finalists consistently demonstrate proactive problem-solving rather than waiting for instructions.

Adaptability: Handling scope changes, pivoting when approaches don’t work, learning new technologies quickly. Engineering projects rarely go exactly to plan—flexibility matters.

Inclusive leadership: Creating environments where diverse team members contribute effectively. RAEng research links inclusive team behaviors to better retention, particularly for women and underrepresented groups.

Resilience under ambiguity: Engineering often involves incomplete information, competing requirements, and uncertain outcomes. Ability to make sound decisions despite ambiguity distinguishes high-performers.

The progression pattern observed:

Early career (0-3 years): Focus on building deep technical competence in core discipline. Employers expect you to solve well-defined problems under supervision.

Mid early-career (3-7 years): Shift toward broader professional skills while maintaining technical credibility. You’re expected to define problems yourself and manage small projects or teams.

Senior/lead roles (7+ years): Balance technical oversight with stakeholder management and commercial thinking. You’re translating between technical realities and business requirements.

Finalists who accelerated progression typically developed professional and behavioral skills alongside technical competence, rather than waiting to “master” technical work before learning communication and leadership. The “double pivot”—technical competence plus professional skills simultaneously—accelerates advancement.

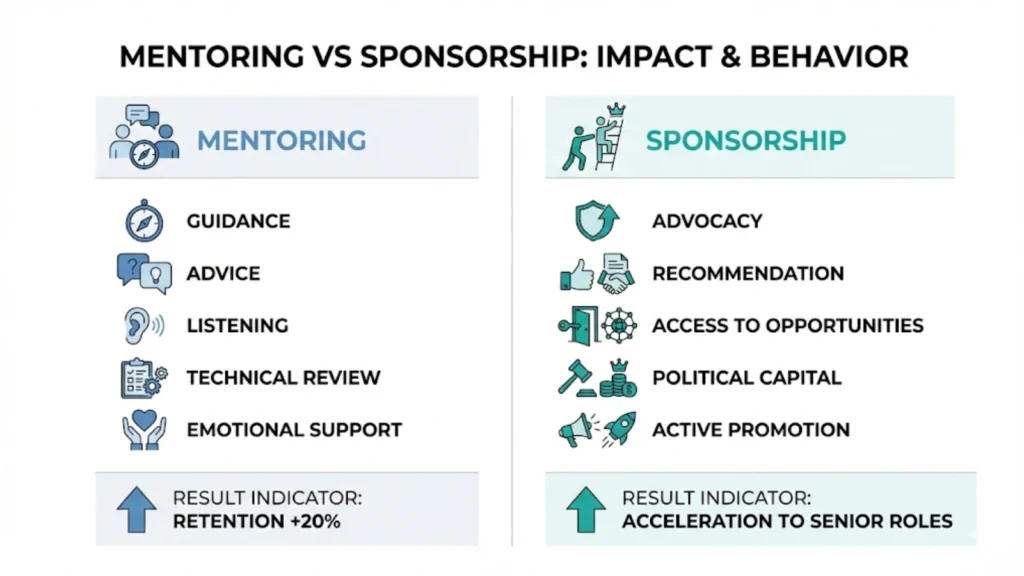

Mentoring vs Sponsorship: Understanding the Difference

The finalists’ narratives frequently mention “mentors” and “supportive networks,” but there’s a critical distinction between mentoring (guidance) and sponsorship (advocacy) that determines career acceleration.

"Mentoring provides valuable guidance—someone to discuss career decisions with, explain industry norms, offer perspective. But sponsorship is what actually opens doors. That's when a senior electrician or contracts manager actively advocates for you—recommending you for complex projects, nominating you for training opportunities, vouching for your readiness for promotion. Early-career engineers, particularly women and underrepresented groups, benefit enormously from sponsors willing to use their influence on your behalf."

Joshua Jarvis, Placement Manager

What mentoring provides:

Career navigation: Advice on which qualifications to pursue, when to seek promotion, how to handle workplace challenges.

Industry context: Explaining unwritten rules, sector-specific norms, realistic timelines for progression.

Technical guidance: Reviewing work, suggesting improvements, answering questions about engineering approaches.

Emotional support: Providing reassurance during difficult periods, normalizing challenges, sharing similar experiences.

What sponsorship provides (and why it’s more powerful for progression):

Active advocacy: Senior leader explicitly recommending you for high-visibility projects, promotions, or development opportunities.

Political capital: Sponsor uses their influence and reputation to vouch for your readiness, convincing other decision-makers to take a chance on you.

Access to opportunities: Sponsor nominates you for roles, training programs, or projects you wouldn’t have known about or been considered for otherwise.

Protection and coaching: Sponsor provides air cover when you make mistakes (expected in stretch assignments), helps you navigate organizational politics, prepares you for senior interactions.

Why the distinction matters for women and underrepresented groups:

RAEng research shows mentoring programs improve retention by up to 20% for women in engineering. However, sponsorship—which requires someone with organizational power actively spending their political capital on your behalf—remains less accessible.

Qualitative signals (X posts, forum discussions) indicate women often receive mentoring (“let me give you advice”) but less frequently receive sponsorship (“I’m putting your name forward for this senior role”). This contributes to slower progression despite comparable or superior technical competence.

How to find mentors:

Professional bodies (IET, IMechE, RAEng) run formal mentoring schemes matching early-career engineers with experienced professionals.

Workplace programs (if your employer offers them)—structured mentoring with defined meetings and goals.

Informal approaches—asking someone whose career path you admire if they’d be willing to meet quarterly for advice.

Alumni networks from your university or apprenticeship provider.

How to find sponsors (harder but more impactful):

Deliver exceptional work: Sponsors risk their reputation recommending you—they need confidence you’ll succeed.

Make your ambitions visible: Sponsors can’t advocate if they don’t know what you want. Express interest in specific roles, projects, or development opportunities.

Build relationships with decision-makers: Sponsorship works when the sponsor actually has influence over opportunities you want. Identify who makes promotion/project decisions and find legitimate ways to demonstrate competence to them.

Ask for specific advocacy: “Would you be willing to recommend me for the [specific project/role]?” is more actionable than “Would you mentor me?”

Be a sponsor for others: As you progress, actively advocate for early-career engineers behind you. This builds reputation as someone who develops talent, which senior leaders value.

The networking infrastructure finalists leveraged:

Professional institutions (IET, ICE, IMechE) provide events, conferences, and committees where early-career engineers meet senior professionals who become mentors and eventually sponsors.

Women’s networks (WES – Women’s Engineering Society, internal company networks) create “protected spaces” where members actively sponsor each other and provide both technical and political guidance.

Industry awards (like Young Woman Engineer) provide visibility that attracts sponsors—senior leaders notice award finalists and often reach out with opportunities.

Understanding how geographic salary variations affect decisions becomes relevant when sponsors advocate for promotions or relocations—knowing regional benchmarks helps you negotiate fairly and make informed career choices.

The practical takeaway: Seek mentors for guidance, but actively identify and cultivate relationships with potential sponsors who have the power to advocate for your progression. For women and underrepresented groups, having even one strong sponsor can compensate for structural barriers that slow progression.

Professional Registration: The Accelerator Most People Ignore

One consistent pattern among finalists: early pursuit of professional registration (EngTech, IEng, or CEng) through the Engineering Council, rather than treating it as “something to do eventually.”

"Professional registration through EngTech, IEng, or CEng requires demonstrating competence against UK-SPEC standards, not just holding qualifications. Early-career engineers who document their CPD systematically—recording specific projects, challenges overcome, skills developed—accelerate their progression significantly. It's the difference between saying 'I have a degree' and proving 'I've successfully delivered these technical outcomes in real environments under supervision.'"

Thomas Jevons, Head of Training

What UK-SPEC actually measures:

UK-SPEC (UK Standard for Professional Engineering Competence) is the framework defining competence requirements for professional registration at three levels:

EngTech (Engineering Technician): Applying proven techniques, contributing to design/development, supervising technical operations.

IEng (Incorporated Engineer): Maintaining and managing applications of current and developing technology, designing/developing operational solutions.

CEng (Chartered Engineer): Developing appropriate solutions to complex engineering problems using new or existing technologies, through innovation and creativity.

Why early registration matters:

Forces systematic competence documentation: Preparing for professional review requires keeping detailed CPD records showing what projects you’ve worked on, what decisions you made, what outcomes resulted, and what you learned. This documentation itself accelerates learning because it requires reflection.

Validates competence independent of employer: If you change jobs, professional registration travels with you. It’s recognized across industries and regions, unlike internal job titles that mean different things at different companies.

Signals commitment and professionalism: Engineering Council statistics show professionally registered engineers earn higher lifetime salaries and progress faster to senior roles, partly because registration signals serious career investment beyond minimum qualification requirements.

Opens specific opportunities: Some roles, particularly in regulated industries or public sector, require or strongly prefer professional registration. Tenders for engineering contracts sometimes require specified percentage of registered staff.

How to approach registration early in your career:

Start documenting from day one: Don’t wait until you “feel ready” for registration. Keep a competence journal recording:

Projects you’ve contributed to and your specific role

Technical challenges you faced and how you solved them

Decisions you made and the reasoning behind them

Skills you developed and how you applied them

Feedback received and what you changed based on it

Map work to UK-SPEC: Review UK-SPEC standards for your target registration level (EngTech, IEng, or CEng) and consciously seek work experiences that build the required competences. If you lack experience in certain areas, ask your manager for opportunities to fill gaps.

Engage with professional body: Join IET, IMechE, or relevant institution early. Student/graduate membership rates are lower, and you get access to mentoring schemes, CPD resources, and registration guidance.

Aim for registration within 3-5 years post-qualification: Finalists who achieved professional registration early (EngTech by year 2-3, IEng by year 4-5) typically progressed faster to senior roles than peers with equivalent technical skills but no registration.

The competence vs qualification distinction:

Engineering Council data shows employers increasingly filter for demonstrated competence (what you can actually do) over pure qualifications (certificates you hold). Professional registration proves competence through:

Portfolio of real project work

Professional review interview assessing technical judgment

Commitment to ongoing CPD (maintaining competence as technology evolves)

Someone with a degree but no systematic work experience documentation struggles to prove competence. Someone with apprenticeship background, strong work portfolio, and EngTech registration clearly demonstrates applied ability.

Common barriers to early registration (and how finalists overcame them):

“I’m not senior enough yet”: Registration levels are designed for different career stages. EngTech is appropriate for technicians and early-career engineers. You don’t need to be “experienced” to start the process—that’s the point of systematic progression through levels.

“It’s expensive”: Professional body membership and registration fees represent investment (£200-400 annually for mid-level membership). However, salary premiums for registered engineers typically recover this within months. Some employers fund membership—ask.

“I don’t have time for CPD”: CPD (Continuing Professional Development) includes work you’re already doing—projects, training, problem-solving. The requirement is documentation, not additional activities. 30 minutes monthly recording what you did and learned satisfies most CPD requirements.

“My employer doesn’t value it”: Engineering Council registration is portable—it benefits your career beyond current employer. If your employer doesn’t value professional development, that’s information about whether to stay long-term.

The practical recommendation: Start CPD documentation now (today, not “when you’re ready”). Review UK-SPEC standards for your target registration level. Join relevant professional body at student/graduate rate. Aim to achieve first registration level (EngTech or IEng depending on starting point) within 3-5 years of entering engineering work.

Barriers Women Face (That Finalists Had to Navigate)

The finalists succeeded within structural barriers that make progression unnecessarily difficult for women in engineering. Understanding what they overcame—rather than just celebrating individual resilience—matters for improving the system.

Retention drop post-age 35:

EngineeringUK data shows 66,000 fewer women aged 35-64 in engineering compared to younger cohorts, indicating significant mid-career dropout. This isn’t because women suddenly lose interest—it’s because retention barriers (inflexible work arrangements, lack of part-time senior roles, caregiving demands coinciding with key career advancement years) force exits.

Finalists who remained in engineering typically had:

- Employers offering flexible working (not just “working from home occasionally” but genuine schedule flexibility)

- Partners sharing caregiving equally, or financial ability to afford external childcare

- Managers actively protecting their career progression during parental leave or reduced hours

Those without these supports often don’t appear in finalist lists—they’ve already left engineering despite equivalent competence.

Male-dominated workplace culture:

IET research indicates 32% of women cite male-dominated culture as a barrier. This manifests as:

Isolation: Being the only woman on site, in meetings, or in department creates “standing out” pressure where mistakes are more visible and credit for successes is less automatic.

Backhanded compliments: “You’re good for a woman engineer” or “I’m surprised you understood that” signal low expectations. Qualitative X signals (finalists and others) report this as motivation fuel but also as emotionally draining constant reminder of not quite belonging.

Assumption of lesser competence: Being asked to take notes in meetings, having ideas attributed to male colleagues who repeat them, needing to prove technical knowledge repeatedly that male peers don’t face.

Site-based challenges: PPE not designed for women’s bodies, inadequate facilities, safety concerns in male-dominated environments where behavior isn’t always professional.

Confidence gap vs competence gap:

ONS data and qualitative research both indicate women apply for promotions or senior roles only when meeting 100% of listed criteria, while men apply at 60% criteria match. This isn’t inherent confidence difference—it’s learned behavior from receiving more criticism for failures and less credit for successes.

Finalists typically overcame this through:

- Explicit encouragement from sponsors saying “you’re ready, apply”

- Protected networks (women’s engineering groups) where they could test ideas without judgment

- Systematic evidence of their competence (documented project outcomes) that countered internal doubt

But the structural issue remains: Organizations lose talented women who are competent but don’t self-promote as aggressively as male peers.

Pay gap persistence:

Gender pay gap in skilled trades reaches 13.9%, with overall engineering gap at 12.8%. This compounds over careers—a 10% pay gap at age 25 becomes £150,000+ lifetime earnings difference.

Factors contributing:

- Women less likely to negotiate starting salaries or raises (again, learned behavior from environments where assertiveness is penalized differently by gender)

- Women more likely to accept lower-paid roles at career re-entry after breaks

- Occupational segregation (women overrepresented in lower-paid engineering roles like technical support vs design)

Finalists who achieved pay parity typically:

- Used professional body salary surveys to establish fair benchmarks

- Negotiated firmly with documented evidence of competence

- Changed employers when pay didn’t reflect contribution (easier with professional registration proving competence)

The “extra work” tax:

Successful women in engineering often get asked to serve on diversity committees, mentor other women, speak at recruitment events, or participate in outreach—valuable work for the profession but unpaid extra labor that doesn’t contribute to promotion criteria focused on technical delivery or project management.

Finalists managed this by:

- Setting boundaries on unpaid diversity work

- Negotiating for diversity/mentoring work to count explicitly toward performance reviews

- Choosing which opportunities aligned with their career goals vs felt obligatory

What finalists did that others might not be able to:

Changed employers when environment was hostile (requires financial stability and confidence other opportunities exist) Invested significant time in professional development and networking (requires employers allowing time and sometimes funding travel/membership) Built strong personal brands through ambassadorship and awards (requires comfort with visibility and employers supportive of external activities)

Understanding what was within individual control (documentation, skill development, seeking mentorship) versus what required supportive structures (flexible employers, financial stability, sponsors willing to advocate) prevents “just work harder” narratives that blame individuals for structural barriers.

Emerging Sectors and Future Skills

The 2025 finalists increasingly work in sectors that barely existed ten years ago or are experiencing rapid transformation.

Renewable energy and sustainability:

Offshore wind, solar infrastructure, battery storage, grid modernization all require electrical, mechanical, and civil engineering expertise. RAEng identifies these as growth areas with projected 21,000 new jobs in regions like West Midlands by 2030.

Skills demand: Power systems design, grid integration, energy storage technologies, lifecycle assessment, regulatory compliance for emerging technologies.

Why women are entering these sectors: Sustainability-focused roles often emphasize purpose-driven work and environmental impact, which research suggests appeals more to women entering engineering than traditional fossil fuel sectors.

Digital-physical integration:

IoT (Internet of Things) connecting physical assets with digital monitoring, “digital twins” (virtual models of real infrastructure), predictive maintenance using sensor data and machine learning.

Skills demand: Data analysis, sensor networks, systems integration, cybersecurity awareness, understanding both physical engineering and software development.

Opportunity: This convergence creates roles for engineers comfortable at the intersection—physical understanding combined with digital literacy. Traditional separation between “mechanical engineering” and “software engineering” is blurring.

Space and aviation innovation:

Commercial space sector expansion (satellite systems, launch infrastructure), aviation decarbonization (electric/hybrid aircraft, sustainable fuels), autonomous systems.

Skills demand: Systems engineering, complex project coordination, regulatory navigation, international collaboration, working with cutting-edge technology where standards don’t yet exist.

Challenge: These sectors are highly competitive and often require advanced degrees or exceptional early-career performance to enter.

Biomedical engineering and healthtech:

Medical devices, assistive technology, healthcare infrastructure, diagnostics equipment—engineering applied to health outcomes.

Skills demand: Cross-disciplinary thinking (engineering + biology/medicine), regulatory compliance (medical device standards), human-centered design, quality assurance.

Gender dynamics: Biomedical engineering shows better gender balance (approximately 30-35% women) than traditional mechanical or electrical engineering, possibly because clear social impact aligns with stated values many women report when choosing careers.

However, policy uncertainty affects career planning in emerging sectors—government commitment to net-zero targets, infrastructure funding, and regulatory frameworks all influence long-term job security and sectoral growth.

AI and automation (not replacing engineers, changing what they do):

Contrary to fears about AI replacing engineers, RAEng research indicates AI tools augment engineering work—automating routine calculations, generating design options, analyzing test data—freeing engineers for higher-level problem-solving and innovation.

Skills demand: Understanding AI capabilities and limitations, working with data scientists, interpreting AI-generated outputs critically, ethics of automated systems in safety-critical applications.

The shift: Engineers increasingly become “AI-assisted problem solvers” rather than “calculation machines.” This elevates the profession toward strategic thinking and creative solutions.

What early-career engineers should prioritize:

Don’t chase specific technologies—chase transferable understanding: Today’s cutting-edge software becomes obsolete in 5-10 years. Understanding systems thinking, problem decomposition, and how to learn new tools matters more than mastering current specific tools.

Build T-shaped skills: Deep expertise in one engineering discipline (the vertical bar of the T) combined with broad understanding across adjacent areas (the horizontal bar). Digital literacy, project management, and communication span all sectors.

Stay curious about emerging applications: Read industry publications, attend webinars, join professional body special interest groups in emerging areas. You don’t need to become expert immediately, but awareness of trends informs career decisions.

Consider purpose-driven sectors: If environmental sustainability or social impact motivates you, sectors like renewable energy, biomedical engineering, or sustainable infrastructure offer engineering career satisfaction beyond just technical challenge.

Document adaptability: When employers evaluate progression to senior roles, demonstrated ability to learn new technologies and adapt to changing requirements matters as much as current expertise. CPD documentation showing continuous learning becomes your evidence.

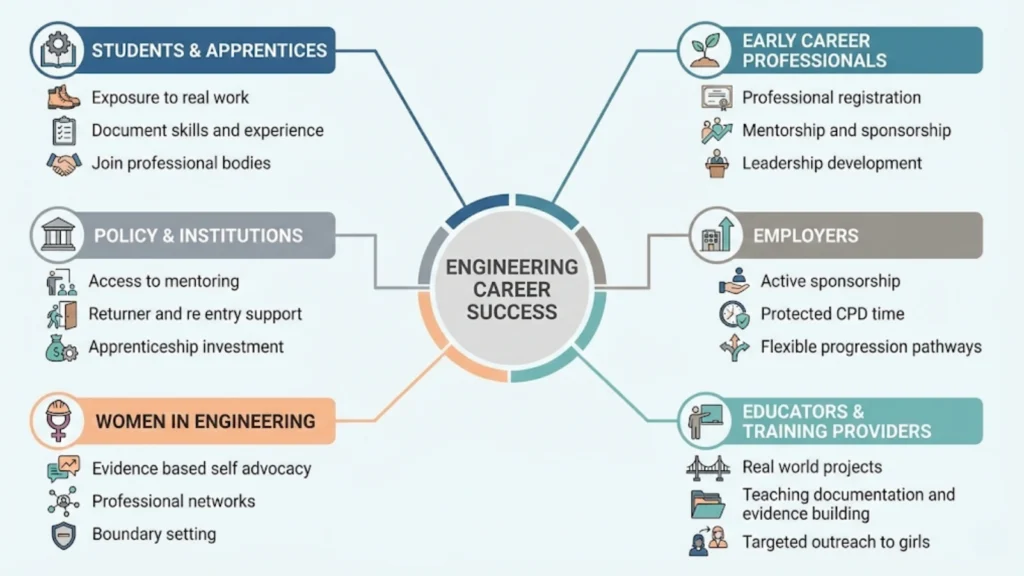

Practical Actions: Translating Finalists' Success Into Your Career

What can you actually do with this analysis?

For students and apprentices (0-2 years in engineering):

Seek broad exposure early: Work across different departments, shadow various roles, volunteer for diverse projects. Early-career breadth helps you identify what engineering work you actually enjoy and where your strengths lie.

Start documenting immediately: Create competence journal from first day of apprenticeship or first job. Record projects, challenges, solutions, skills developed. This becomes foundation for professional registration and promotion applications.

Join professional body at student rate: IET, IMechE, or discipline-relevant institution. Attend events, access resources, make connections before you “need” them for career advancement.

Build portfolio of work: Collect examples of your engineering output (with employer permission, respecting confidentiality). Drawings, calculations, reports, photos of installations—evidence of competence beats CV claims.

For early-career engineers (2-7 years post-qualification):

Pursue professional registration systematically: Review UK-SPEC standards for EngTech or IEng. Map your current competences against requirements. Identify gaps and seek work assignments that build missing areas.

Find mentor AND sponsor: Use professional body mentoring schemes for guidance. Identify potential sponsors (senior engineers with influence over opportunities you want) and make your career ambitions visible to them.

Take on small leadership: Volunteer to lead minor projects, coordinate activities, mentor apprentices. Build leadership evidence before waiting for “official” management role.

Develop T-shaped skills: Deepen expertise in core discipline while building breadth in project management, commercial awareness, and emerging digital technologies.

For employers and managers:

Structure sponsorship, not just mentoring: Explicitly advocate for high-potential early-career engineers—recommend them for stretch projects, nominate for development programs, vouch for readiness during promotion discussions.

Make CPD documentation part of regular work: Provide 15-30 minutes monthly for engineers to update competence journals during working hours. This isn’t “extra”—it’s essential career development that benefits employer through retained talent.

Offer flexible progression pathways: Not everyone wants traditional management. Create technical specialist and project leadership routes alongside people management careers.

Support professional registration: Fund professional body membership, provide study time for registration preparation, celebrate achievement of EngTech/IEng/CEng publicly.

Address retention barriers proactively: Flexible working for everyone (not just women), part-time senior roles, returnship programs after career breaks, explicit policy against “extra work” diversity tax without recognition.

For educators and training providers:

Integrate real-world projects early: Don’t wait until final year for industry connection. Bring live engineering challenges into curriculum from year one, even if simplified.

Teach competence documentation: Show students how to maintain CPD records, map work to UK-SPEC standards, build portfolios. These are career-critical skills rarely taught explicitly.

Connect students with professional bodies: Facilitate IET/IMechE student membership, bring professionals into classroom, organize site visits to show what engineering work actually involves.

Target girls specifically: Engineering UK data shows girls’ interest (23%) trails boys’ (52%). Run targeted programs addressing confidence gaps, provide female role models, explicitly counter stereotypes about “who belongs” in engineering.

For women navigating barriers:

Document competence systematically: Counter bias with evidence. Detailed project records, quantified outcomes, testimonials from clients/colleagues make it harder for doubters to dismiss your contributions.

Build strong networks: Join WES (Women’s Engineering Society), company women’s networks, professional body diversity groups. These provide both emotional support and strategic career guidance.

Set boundaries on unpaid diversity work: It’s okay to decline some requests. When accepting, negotiate for recognition—”I’ll lead this initiative if it counts toward my performance review explicitly.”

Change employers when necessary: If environment is persistently hostile despite your efforts and organization isn’t changing, your skills are valuable elsewhere. Don’t stay out of misplaced loyalty to toxic situations.

For policymakers and funders:

Expand access mentoring and sponsorship: Fund programs specifically connecting early-career engineers from underrepresented groups with senior sponsors willing to advocate for their progression.

Support return-to-work programs: Mid-career retention requires pathways back after breaks. Fund returnships, part-time training updates, childcare support for professional development.

Increase apprenticeship capacity: DfE data shows apprenticeships yield outcomes comparable to degrees but with lower gender pay gap. Expanding access—particularly for women and working-class students—improves diversity at entry level.

The replication principle:

Finalists’ individual circumstances may not be replicable (supportive employers, financial stability, access to networks). But their behaviors are: systematic documentation, early professional engagement, seeking mentorship, building evidence of competence, strategic visibility through ambassadorship and awards.

Focus on behaviors you can control while advocating for structural changes that reduce barriers for those following behind you.

Moving Beyond Individual Resilience Stories

The 2025 Young Woman Engineer finalists deserve celebration for navigating challenging paths successfully. But framing their success purely as individual achievement—”they worked hard, so can you”—misses the structural analysis that actually helps others.

What we learned that’s genuinely useful:

Hybrid pathways work: Combining academic and vocational training, degrees with substantial placements, or apprenticeships followed by part-time degrees produces versatile engineers employers value highly.

Early professional registration accelerates progression: Systematic CPD documentation from day one, pursuing EngTech/IEng/CEng within 3-5 years post-qualification, forces competence building and proves capability.

Sponsorship matters more than mentoring: Guidance helps, but active advocacy from senior professionals with organizational power actually opens doors to opportunities and advancement.

Documentation proves competence: Detailed records of projects, decisions, outcomes, and learning create evidence that overcomes bias and supports promotion cases far better than claims without proof.

Networks aren’t optional: Professional body membership, women’s engineering groups, ambassador roles all provide connections, guidance, and visibility that accelerate careers.

What we learned about barriers that need fixing:

Mid-career retention crisis: 66,000 fewer women aged 35-64 indicates systemic failure, not individual choice. Organizations lose talent they invested years developing because they won’t provide flexible senior roles or equitable progression during caregiving years.

Confidence gaps are learned, not innate: Women applying only when meeting 100% of criteria vs men at 60% reflects environments where women receive more criticism for failures and less credit for successes—organizational culture problem, not individual psychological issue.

Extra diversity work taxes women: Successful women get asked to mentor, serve on committees, recruit others—valuable profession-building work but often unpaid and not counted toward promotion criteria focused on technical delivery.

Pay gaps compound over careers: 12.8-13.9% gaps persist despite equal competence, creating £150,000+ lifetime earnings differences that discourage persistence and signal women’s contributions aren’t valued equally.

Call us on 0330 822 5337 to discuss engineering career pathways, understand how electrical trades apprenticeships compare to traditional engineering degrees, explore mentoring and sponsorship opportunities for early-career technical professionals, and assess whether vocational routes or academic pathways better suit your circumstances and career goals.

What we’re not going to tell you:

- That working hard guarantees awards or recognition (selection bias toward already-high-achievers)

- That individual resilience solves structural barriers (retention failures indicate systemic problems)

- That everyone can replicate finalists’ circumstances (supportive employers, financial stability, strong networks aren’t universally available)

- That engineering careers are easy for women if you just “be confident” (barriers are real, documented, and require organizational change)

What we will tell you:

- How systematic CPD documentation from day one creates evidence supporting professional registration and promotion applications regardless of education pathway

- Why pursuing EngTech/IEng/CEng within 3-5 years post-qualification accelerates progression compared to waiting until you “feel ready”

- How to identify and cultivate sponsor relationships beyond just finding mentors who provide guidance but not active advocacy

- What UK-SPEC standards actually require and how to map workplace projects to competence criteria systematically

- Why apprenticeship outcomes (retention rates, earnings, progression speed) are increasingly comparable to traditional degrees when structured properly

- How women’s engineering networks (WES, professional body diversity groups) provide both support and strategic career advantage

- What “T-shaped skills” means practically—deep technical expertise in one area plus broad understanding across adjacent disciplines, project management, and communication

- Why flexible working and part-time senior roles aren’t “accommodations” but retention strategies preventing mid-career talent loss

- How to negotiate fairly using professional body salary surveys and documented competence evidence to counter pay gaps

- What emerging sectors (renewables, digital-physical integration, biomedical) offer better gender balance and purpose-driven work many engineers value

For early-career engineers: Build evidence systematically through CPD documentation, pursue professional registration early, seek sponsors not just mentors, develop T-shaped skills combining technical depth with professional breadth, join professional bodies for networking and credibility.

For employers: Move from mentoring programs to active sponsorship, fund professional body membership and CPD time, create flexible progression pathways including technical specialist and project leadership routes not just management, address retention barriers proactively through flexible working at all levels, recognize diversity work explicitly in performance reviews.

For educators: Integrate real-world projects early, teach competence documentation as core skill, connect students with professional bodies from year one, target girls specifically with interventions addressing confidence gaps and providing role models, facilitate hybrid pathways combining academic depth with workplace competence.

No promises that hard work alone overcomes structural barriers. No suggestions that finalists’ success proves the system works fine. Just honest analysis of replicable behaviors that accelerate progression within imperfect structures, while acknowledging the system-level changes needed so future engineers don’t face the same unnecessary obstacles.

References

Primary Official Sources

- EngineeringUK Engineering and Technology Workforce May 2025 Update: https://www.engineeringuk.com/research-and-insights/our-research-and-evaluation-reports/engineering-and-technology-workforce-may-2025-update

- ONS Gender Pay Gap in the UK 2025: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/bulletins/genderpaygapintheuk/2025

- ONS UK Labour Market December 2025: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/bulletins/uklabourmarket/december2025

- UK Government Occupations in Demand 2025: https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/occupations-in-demand/2025

Industry Standards and Research

- Royal Academy of Engineering Diversity in Engineering: https://raeng.org.uk/programmes-and-prizes/programmes/uk-grants-and-prizes/support-for-research/access-mentoring

- IET Women in Engineering Statistics and Research: https://www.theiet.org/impact-society/diversity-inclusion/women-in-engineering

- EngineeringUK Diversity Dashboard November 2025: https://www.engineeringuk.com/research-and-insights/our-research-and-evaluation-reports/diversity-infographic-dashboard

- RAEng Research Fellowships and Early-Career Support: https://raeng.org.uk/programmes-and-prizes/programmes/uk-grants-and-prizes/support-for-research/research-fellowships

- Engineering Council UK-SPEC Professional Standards: https://www.engc.org.uk/standards-guidance/standards/uk-spec/

Professional Development Resources

- Institution of Engineering and Technology (IET) Career Support: https://www.theiet.org/career/

- Women’s Engineering Society (WES): https://www.wes.org.uk/

- Young Woman Engineer Awards 2025 Finalists: https://youngwomenengineer.theiet.org/

Labour Market Analysis

- Department for Education Apprenticeship Outcomes: https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/

- ONS Labour Force Survey Engineering Occupations Data: https://www.ons.gov.uk/surveys/informationforbusinesses/businesssurveys/labourforcesurvey

Note on Accuracy and Updates

Last reviewed: 03 February 2026. This page is maintained; we correct errors and refresh sources as workforce statistics, professional registration requirements, and engineering sector developments change. Key statistics—women at 16.9% of UK engineering workforce (6.4 million total), 66,000 mid-career retention drop, gender pay gaps 12.8-13.9%, girls’ interest 23% vs boys’ 52%, apprenticeship starts 17% women—reflect EngineeringUK May 2025 data and ONS 2025 releases. Professional registration guidance (UK-SPEC standards, EngTech/IEng/CEng requirements) aligns with Engineering Council current frameworks. Mentoring impact (20% retention improvement), skills demand trends, and sectoral projections (21,000 green jobs West Midlands by 2030) come from RAEng research and regional authorities. Analysis of 2025 Young Woman Engineer finalists represents qualitative lens supported by Tier 1/2 evidence, acknowledging selection bias toward high-achievers. Next review scheduled following EngineeringUK 2026 workforce update or significant policy changes affecting engineering education pathways.