Engineering Project Management: Learning from the Hoover Dam’s Lasting Legacy By Charanjit Mannu (Vocational Education, Employability & Green Technology)

- Technical review: Thomas Jevons (Head of Training, 20+ years)

- Employability review: Joshua Jarvis (Placement Manager)

- Editorial review: Jessica Gilbert (Marketing Editorial Team)

- Last reviewed:

- Changes: Updated with modern UK electrical training frameworks and CDM regulation references

The Hoover Dam gets referenced constantly in project management circles, usually with the same tired narrative about “when projects were done properly” or “before regulations slowed everything down.” Strip away the nostalgia, though, and you’re left with something more useful: a 1930s megaproject that pioneered integrated delivery under extreme constraints, killed 96 confirmed workers in the process, and created lessons we’re still applying in modern construction and installation work today.

Here’s the thing about learning from historical projects. The Hoover Dam isn’t valuable because they “built things better back then” (they didn’t, really). It’s valuable because it demonstrates what happens when you push engineering limits without safety frameworks, what works when you sequence dependencies properly, and how project management principles apply whether you’re diverting the Colorado River or installing electrical systems in a commercial property.

This isn’t about romanticizing the past. It’s about extracting transferable insights from a project that operated under completely different rules, then understanding which principles survived the transition to modern regulated work and which practices would get you prosecuted today.

The Historical Reality: What the Hoover Dam Actually Was

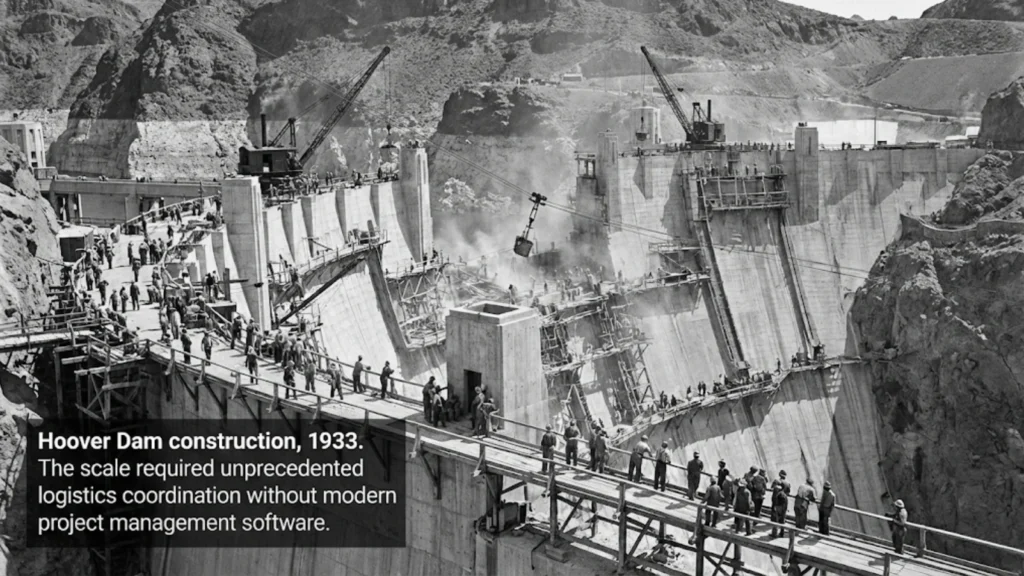

The Hoover Dam (1931-1936) emerged during the Great Depression as federal intervention to control Colorado River floods, provide irrigation, and generate hydroelectric power. The scale was unprecedented: 726 feet high, 1,244 feet across Black Canyon, using 4.4 million cubic yards of concrete. Workforce peaked at 5,218 workers, with over 21,000 employed overall throughout the project.

The contract went to Six Companies Inc., a consortium formed specifically for this project, for $48.9 million with heavy penalties for delays and bonuses for early completion. They finished two years ahead of schedule through 24/7 shifts and aggressive risk management that prioritized deadlines over worker safety.

The project built an entire town (Boulder City) for 5,000 workers, constructed 22.7 miles of railroad for materials transport, and excavated four 56-foot-diameter tunnels to divert the river before construction could begin. Every logistical element required coordination without digital modeling, supply chain software, or modern communication systems.

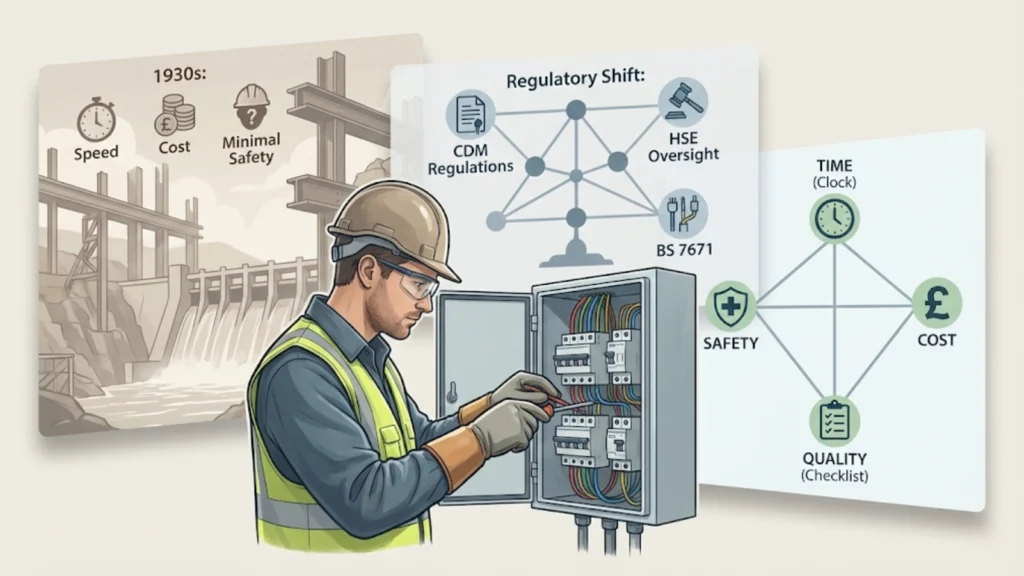

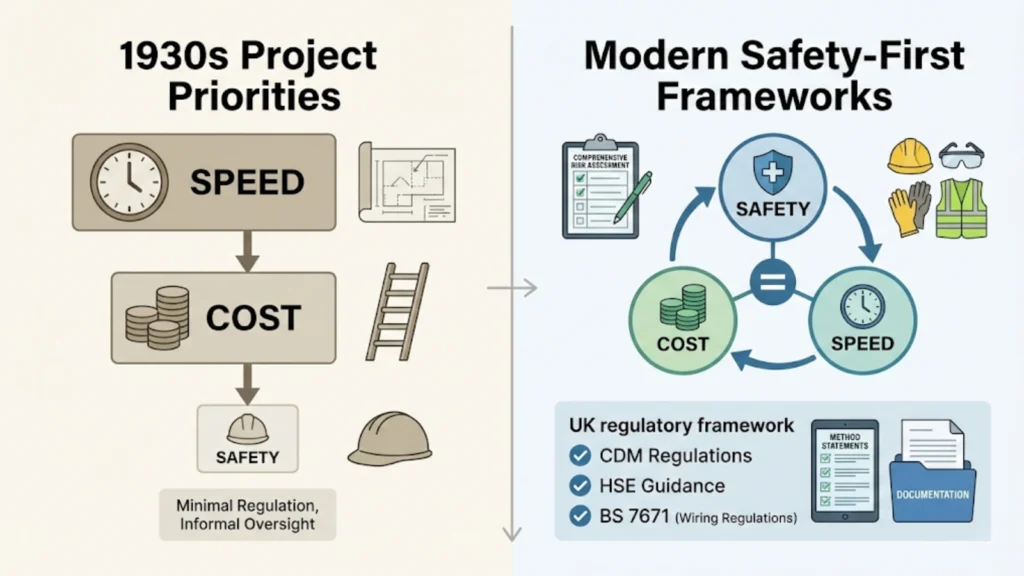

Context matters enormously here. This was 1930s America during economic collapse. Labor was abundant and desperate. Safety regulations barely existed. Environmental impact assessments weren’t required. The regulatory landscape that governs modern construction simply wasn’t there. Understanding that gap matters because it shows how far professional standards have evolved and why modern residential fire safety installation laws represent specific, enforceable requirements that didn’t exist during projects like the Hoover Dam, ensuring life safety through mandated compliance rather than optional best practices.

What Still Applies: Project Management Principles That Survived

Work breakdown structures divided the Hoover Dam into distinct phases: river diversion, foundation excavation, concrete pouring in interlocking blocks, powerhouse installation. This aligns perfectly with modern PMBOK decomposition techniques. Breaking complex projects into manageable work packages isn’t revolutionary now, but systematically applying it on that scale in 1931 was pioneering.

Sequencing dependencies followed rigid logic. The Colorado River had to be diverted through tunnels before foundation excavation could begin. Concrete couldn’t be poured until aggregates were produced on-site. Each phase created prerequisites for the next. This mirrors critical path methodology that modern scheduling software automates, but the principle remains identical.

On-site manufacturing reduced supply chain risk dramatically. Six Companies built aggregate plants, concrete mixing facilities, and steel fabrication shops directly at the construction site. This is the 1930s equivalent of modern just-in-time supply strategies and off-site manufacture approaches. Control your critical dependencies or accept the risk of external delays disrupting your timeline.

Risk identification happened early through geological surveys assessing foundation conditions, seismic activity, and rock stability. The surveys informed engineering decisions before major commitments were made. This parallels systems engineering’s hazard analysis and modern risk registers, just without the formal documentation frameworks.

Accountability structures mattered. The consortium model spread financial risk across multiple companies while federal oversight provided governance. Modern megaproject governance models use similar structures, balancing contractor incentives with regulatory oversight to manage both delivery and compliance.

The concrete cooling system demonstrated genuine innovation solving thermal problems. Mass concrete pours generate heat that can cause structural cracks. The project embedded cooling pipes in concrete blocks, circulating refrigerated water to control curing temperatures. When physical constraints threaten engineering integrity, the solution is technical intervention, not just adding labor or accepting defects.

To be fair, these weren’t entirely new concepts even in 1931. But applying them systematically at this scale, documenting the approach, and proving the principles worked created the foundation for modern project controls frameworks.

The Unacceptable Practices: Why Modern Standards Exist

Safety standards at the Hoover Dam would trigger immediate site shutdowns today. Workers died from falls, equipment accidents, heat exposure, and carbon monoxide poisoning in tunnels (often misdiagnosed as pneumonia). High-scalers worked without harnesses. Tunnel drilling exposed workers to silica dust without respiratory protection. Heat regularly exceeded 120°F with minimal hydration or rest requirements.

The official death toll sits at 96 confirmed industrial fatalities, but this likely undercounts heat-related deaths and respiratory disease from silica exposure that manifested later. Modern construction operates under the “Zero Harm” principle where every accident represents a systems failure requiring investigation and correction. A single fatality triggers total site shutdown and regulatory investigation under current HSE frameworks.

Thomas Jevons, Head of Training at Elec Training, puts this in perspective:

"People romanticize the 'get it done' mentality of projects like the Hoover Dam, but 96 confirmed deaths tell a different story. CDM regulations and electrical installation standards emerged because unregulated work killed people. They're technical solutions to engineering problems, not administrative burdens."

Thomas Jevons, Head of Training at Elec Training

Environmental impact assessment didn’t exist. The dam proceeded without studying downstream effects on the Colorado River Delta ecosystem or long-term sedimentation patterns in Lake Mead. Modern projects require comprehensive Environmental Impact Statements before approval, with ongoing monitoring throughout construction and operation.

Labor practices excluded Chinese workers and limited opportunities for minorities. Modern anti-discrimination law makes such exclusions prosecutable offenses. Worker welfare provisions were minimal. The initial “Ragtown” settlement lacked basic sanitation until federal intervention. Modern projects require Worker Welfare Standards under IFC Performance Standards before construction begins.

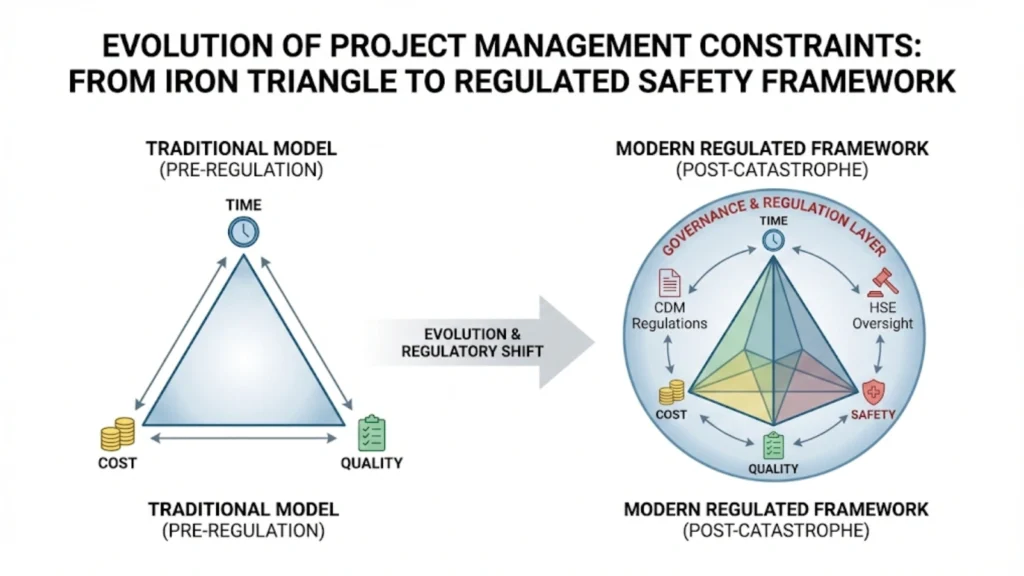

The regulatory shift represents evolution in professional accountability. Frank Crowe, the project manager, was accountable primarily for schedule and budget. Modern Principal Contractors and Lead Designers carry legal “Duty of Care” where safety performance weighs equally with financial performance under CDM Regulations.

Systems Integration: Why Modern Engineering Demands Holistic Thinking

The Hoover Dam wasn’t just a concrete barrier. It functioned as an integrated system: hydroelectric generation, water storage, flood control, and irrigation supply operating simultaneously. The structure, turbines, electrical systems, and water management components had to work together as a complete machine, not isolated elements.

This systems thinking applies directly to modern electrical installation work, regardless of scale. A domestic installation isn’t just circuits. It’s load calculation, protective devices, earthing systems, and bonding working as integrated protection against shock and fire. Get one element wrong and the entire system’s safety is compromised.

Commercial and industrial installations increase complexity but follow identical principles. Understanding how distribution boards, isolation procedures, testing sequences, and certification requirements connect ensures installations function safely under real-world conditions. The competency requirement isn’t memorizing regulations: it’s understanding how systems interact.

Modern qualification pathways through JIB cards demonstrate this systems approach to competency development. The progression through Level 2, Level 3, NVQ portfolios, 18th Edition, and AM2 assessment builds understanding layer by layer. Each stage adds knowledge that connects to previous learning, creating comprehensive competency rather than isolated skills.

The Hoover Dam proved that large-scale engineering requires coordination across disciplines. Civil, mechanical, and electrical engineers had to align their work through the project timeline. Modern Building Information Modeling (BIM) formalizes this coordination, but the underlying principle remains unchanged: integrated systems require integrated planning.

The Skills Gap: Then and Now

Workforce development at the Hoover Dam followed a harsh model. Workers learned through direct exposure to hazardous conditions. The “sink or swim” approach meant those who adapted quickly survived, while others got injured or left the project. Training was minimal, supervision focused on productivity rather than safety, and competency was measured purely by ability to complete work quickly.

This created efficiency in the short term. Workers who couldn’t handle conditions self-selected out. Those who remained developed genuine competency through repeated exposure. But the human cost was substantial, and many injuries occurred during the learning curve when proper training would have prevented accidents.

Modern workforce development evolved from recognizing this model’s failures. Structured training combines theoretical knowledge with practical application under supervision, ensuring learners develop competency before facing complex or hazardous work independently.

Joshua Jarvis, Placement Manager at Elec Training, explains the business case that changed employer attitudes:

"The Hoover Dam had unlimited desperate workers during the Depression. Today's skills shortages mean employers can't afford high turnover from preventable accidents or incompetent work. They want people who've been trained properly, not just cheaply. The business case for proper training is stronger now than ever."

Joshua Jarvis, Placement Manager

The electrical installation sector demonstrates this evolution clearly. Short course providers still market five-week routes to “qualified electrician” status, echoing the Hoover Dam’s rapid exposure model. But employers increasingly reject candidates without proper NVQ portfolios and AM2 passes because they’ve learned that shortcuts create liability, not competency.

Proper formal apprenticeship routes building competency take longer precisely because they replace dangerous trial-and-error with supervised progression. Apprentices combine classroom theory with on-site experience under qualified electricians, developing understanding before facing high-risk scenarios alone.

The skills shortage adds urgency but doesn’t justify cutting corners. Employers facing recruitment difficulties need workers who won’t cause expensive mistakes, regulatory violations, or safety incidents. Someone properly trained through Level 2, Level 3, NVQ, and AM2 represents lower long-term risk than someone pushed through accelerated courses without verified competency.

Risk Management and Delivery Pressure: The Cost of Speed

The Hoover Dam finished two years early through aggressive schedule management: 24/7 triple shifts, financial penalties for delays, bonuses for early completion, and accepting higher accident rates as inevitable costs of maintaining pace.

This created a fundamental trade-off. The consortium prioritized speed to minimize burn rate and maximize completion bonuses. Safety measures that slowed work were considered negotiable. Workers understood that questioning safety meant losing employment, so incident reporting was minimal and hazards went unaddressed.

Modern project controls frameworks recognize this creates a “safety-quality-speed” trilemma. Pushing too hard on schedule creates quality debt (defects requiring expensive rework) and increases incident rates. Earned Value Management and similar methodologies use data to ensure acceleration doesn’t compromise other project objectives.

The CDM Regulations specifically address this by placing legal duty on Principal Contractors and designers to manage construction risks throughout the project lifecycle. Schedule pressure doesn’t justify unsafe practices because regulatory penalties now exceed any timeline bonuses.

To be fair, the Hoover Dam’s schedule achievement was impressive engineering. Two years ahead of a five-year contract demonstrates exceptional coordination and execution. But the methods used would be criminally prosecuted today, and the approach created technical debt through rushed work that caused long-term maintenance issues.

Modern projects learn from this by building contingency into schedules, using simulation to test acceleration scenarios before implementing them, and monitoring leading indicators (near-miss reports, minor injuries, quality deviations) that predict whether pressure is creating unsustainable risk.

The key lesson isn’t “don’t push schedules.” It’s “understand what you’re trading when you accelerate, and don’t accept trades that kill people or create catastrophic failures.”

Transferable Lessons for Modern Construction and Installation

The Hoover Dam’s relevance to today’s electrical installation work and construction projects lies in specific transferable principles, not general inspiration about “how they built back then.”

Planning prevents problems. Comprehensive site surveys, risk assessments, and logistics planning before work begins saves time and money during execution. This applies whether you’re diverting a river or planning cable routes in a commercial installation. Understanding constraints upfront prevents expensive mid-project discoveries.

Dependencies must be sequenced properly. You can’t pour concrete before excavation completes. You can’t commission circuits before testing verifies isolation procedures. Critical path thinking identifies which activities gate progress, allowing resources to focus where delays hurt most.

Innovation solves technical constraints. The cooling pipe system emerged because thermal physics threatened concrete integrity. Modern electrical work requires similar problem-solving when existing infrastructure creates challenges for new installations. Innovation means understanding constraints well enough to engineer solutions, not just following standard approaches.

Integration requires coordination. The Hoover Dam integrated hydroelectric generation with water management and flood control. Modern installations integrate circuits, earthing, protection, and distribution. Success requires understanding interfaces between systems, not just individual components.

Competency can’t be shortcut. The Hoover Dam’s casualties proved that throwing untrained workers at complex problems costs lives. Modern electrical installation requires verified competency through NVQ portfolios and AM2 assessment because electrical faults kill people and create fires. Proper training takes time because safety can’t be rushed.

Accountability structures prevent failures. Clear responsibility for safety, quality, and delivery creates pressure to maintain standards. Modern CDM Regulations assign specific duties to Principal Contractors, designers, and workers because diffused accountability leads to preventable incidents.

FAQs

Several myths around the Hoover Dam deserve addressing before concluding.

Myth: “They built better quality back then.”

Reality: They built thicker because stress calculations were less precise. Modern engineering achieves equivalent safety factors with 30% less material through better modeling and materials science. Quality improved through understanding, not declined through regulation.

Myth: “Regulations are why modern projects are slower.”

Reality: Modern projects account for total lifecycle costs including decommissioning and environmental restoration that the Hoover Dam ignored. Longer timelines reflect broader scope, not inefficiency. When comparing equivalent scopes, modern projects match or exceed historical pace.

Myth: “Workers were buried in the concrete.”

Reality: This is physically impossible for gravity dam construction. Concrete was poured in small interlocking blocks, and the heat from curing would have destroyed remains while compromising structural integrity. This myth persists despite being definitively disproven.

Myth: “Hero engineers delivered projects alone.”

Reality: The consortium model proves success came from team coordination across multiple companies and disciplines. Frank Crowe gets credit as project manager, but delivery required thousands of workers, engineers, and supervisors executing coordinated plans.

For electrical installation professionals, apprentices, and those considering the trade, the Hoover Dam offers useful lessons:

First, proper planning and sequencing apply at every scale. A domestic rewire requires similar dependency thinking as a megaproject, just compressed in scope. Understanding which work must complete before other activities begin prevents expensive rework and delays.

Second, competency frameworks exist because unregulated work kills people. The progression through Level 2, Level 3, NVQ, and AM2 isn’t arbitrary bureaucracy. It’s the electrical sector learning from decades of incidents what knowledge electricians need before working independently on installations that create shock and fire risks.

Third, systems thinking matters more than component knowledge. Understanding how circuits, earthing, bonding, and protective devices interact as complete systems ensures installations function safely under real-world conditions, not just pass inspection.

Fourth, shortcuts create liability. The Hoover Dam’s casualties prove that accepting risk to save time costs more than proper approaches. Employers increasingly recognize that properly trained electricians create less long-term risk than candidates from short courses without verified competency.

Fifth, innovation solves constraints. Whether it’s cooling pipes in concrete or creative cable routing in challenging installations, understanding problems deeply enough to engineer solutions distinguishes competent professionals from those just following standard procedures.

The Hoover Dam isn’t a model to replicate. It’s a case study demonstrating what worked (integrated planning, dependency sequencing, innovation under constraints), what failed catastrophically (prioritizing speed over safety), and how professional standards evolved to prevent repeating the failures while preserving the successful principles.

Modern electrical installation work benefits from this evolution. Structured training pathways, competency verification through NVQ and AM2, regulatory frameworks ensuring safety, and employer expectations for proper qualifications all emerged from learning what happens when industries lack these protections.

Understanding that history makes the current qualification requirements sensible rather than burdensome. They’re not obstacles preventing people from becoming electricians. They’re safeguards ensuring electricians develop genuine competency before facing situations where mistakes kill people or create fires.

That’s the real lesson from the Hoover Dam: engineering excellence requires both technical innovation and professional standards that protect workers and end-users. Modern construction and installation sectors learned to balance both, creating safer industries without sacrificing capability.

Call us on 0330 822 5337 to discuss how structured training pathways build genuine competency for modern electrical installation work. We’ll explain the progression through Level 2, Level 3, NVQ, and AM2 assessment, what our in-house recruitment team can do to secure placement support for portfolio completion, and why employers increasingly demand properly qualified electricians rather than short-course candidates. No hype. No shortcuts. Just practical guidance on qualification routes that lead to sustainable careers in the electrical installation sector.

References

- US Bureau of Reclamation: Hoover Dam History and Construction Records – https://www.usbr.gov/lc/hooverdam/history/

- ASCE Historic Civil Engineering Landmark: Hoover Dam – https://www.asce.org/about-civil-engineering/history-and-heritage/historic-landmarks/hoover-dam

- National Archives: Hoover Dam Project Records – https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2003/summer/hoover-dam.html

- Institution of Civil Engineers: Hoover Dam Case Study – https://www.ice.org.uk/what-is-civil-engineering/what-do-civil-engineers-do/hoover-dam/

- UK Health and Safety Executive: Construction (Design and Management) Regulations 2015 – https://www.hse.gov.uk/construction/cdm/2015/index.htm

- IET Wiring Regulations BS 7671:2018+A2:2022 – https://www.theiet.org/

- City & Guilds: NVQ Level 3 Electrical Installation Qualification Framework – https://www.cityandguilds.com/

Note on Accuracy and Updates

Last reviewed: 5 February 2026. This article references historical construction project management practices and connects them to modern UK electrical installation training standards. Historical data sourced from US Bureau of Reclamation archives and ASCE documentation. UK training frameworks verified against current City & Guilds and ECS/JIB requirements. We update this content as qualification standards and regulatory frameworks evolve.